Paintings →

The Past of the Future

Text by MIKA HANNULA

What happens when we try to visualise our relationship to the past? Is it possible to come to terms with the past without becoming excessively sentimental and egoistical? What do we remember when we go back in time to when we were kids, adolescents, young adults? And how do these memories influence what we think about ourselves here and now?

This is just what Jarmo Mäkilä’s exhibition The Men’s Room is all about: it is in every sense and nuance a coming to terms with the past. It is arguing and discussing, disputing and caring, it is the disproportionateness of things and their contextual proportioning. In style it is comprehensive and total, but by no means fatal. Mäkilä starts with his childhood, his relationship to his late father, his personal and artistic development. He does not embellish or conceal, neither does he glorify his link to that which was and never will return, but which is always present.

Mäkilä’s exhibition is an exceptionally lucid, logical and compact totality. It is just what it purports to be and nothing else: a Gesamtkunstwerk with all its imperfections, contradictions and confl icts, whether examined thematically or for its myriad forms of expression. It does not seek to cover the whole theme (of coming to terms with the past) from front to back and inside out, but offers an opportunity to treat the subject through multi-dimensional experience and see how relations between different subjects and signifi ers form and develop.

But what is it with Mäkilä in this process; this coming to terms with the past?

Both in principal and practice, Mäkilä provides a credible and critically constructive interpretation of what this coming to terms with the past is all about. He goes somewhere, but is unwilling to remain a prisoner to its sad warmth. The paintings, drawings, cartoons, installations and sculptures in the exhibition do not lead to a dead end, neither do they repeat themselves or sink into narcissistic howls.

And what is more important, Mäkilä does not describe his past because it’s somehow fun or great, but because he has no other alternative. It is more of an obsession than a pleasure in which the relationship to the past is motivated by individual self-interest.

In this process relations are worked through in order to obtain even a little help towards understanding who you are, where and how. A process constructed and realised as a dialogue between these three intertwined yet nevertheless separate time zones. Not in the way we see the past, present and future, but defi nitely in the way these three zones infl uence and fashion each other.

What Mäkilä is doing is very close to what the great psychiatrist Sigmund Freud wrote about the subject in a short essay in late 1914: the whole way of thinking about and the reason for coming to terms with the past are encapsulated in the title Erinnern, Wiederholen und Durcharbeiten – remembering, repeating and workingthrough. Not, however, in such a way that the result is a neat little package that can be lightly discarded on the rubbish dump of history in order to allow us to concentrate on the dizzying achievements of tomorrow, but that the process is by nature continuing, endless and utterly exhausting.

Well, basically it’s all about this tackiness and diffi culty. Coming to terms with the past is not real if it degenerates into developing euphoria or coquetting melancholia. Mäkilä returns to somewhere that was, but which changed when he was elsewhere. His journey is by no means easy, neither physically or mentally, nor is it an easy one in relation to his father or himself. During this journey it thundered and rained, snowed and hailed, mentally speaking. It’s a journey that can be articulated with the help of Freud and the views and ideas of Paul Gilroy on coming to grips with his own personal past as expressed in his theory of postcoloniality.

Gilroy describes the relationship between his physical origins and destination as a struggle. However, it is not essential how the various signifi ers are defi ned, but how they affect each other. For Gilroy, post-coloniality means coming to terms with the past as a process in which we must be able, simultaneously, to handle and maintain that where we came from and how we are striving to go from there to somewhere else. Here we are not hunting for truths but seeking, experimenting and testing committed interpretations. Thus it’s a matter of the permanent and challenging simultaneity of the origins of our identity and the path of its development – the roots and the routes. The content and meaning of this journey is strongly infl uenced by our attitude to where we have come from and to where we are going, sometimes stumbling, sometimes swinging on our heels.

This collision between the past and the present (in which the only thing certain is uncertainty) is just what Mäkilä so well expresses in his exhibition. Not as a ready-made product but a mere suggestion, alas one that is damaged and deformed. It is a painfully beautiful journey, which is present in the whole and the details. It extends from raw physicality to conscious fl irting with pathos. And visually it carries the subject both forward and downwards.

It is present as two very special sculptures. We look and circle around two different miniatures, which though shown apart are inevitably linked together. We can see – gazing down from on high at the whole and the details – both the artist’s childhood home and his school. The structures of the past, though destroyed, never leave you alone.

The past, which the fi re doesn’t destroy, neither does it spoil. The past is not just a stain on the cerebral cortex, but lives and throbs with the power of muscular memory, thousands of times with all the conviction of reunion. Past experiences turn into fl esh and sweat, becoming a moribund mass. Not generally, but always privately, personally. We can see works of art, which look like they’ve been made to kick around; so very vulnerable, so easily destroyable – yet standing independently on their own like they’ve been buried alive. For ever on the move yet always returning. The past is present in a series of drawings that almost, if not quite, become a part of our skin, part of a culminating series of experiences in which the wounds are festering and vulnerability is not the exception but the norm. Even so, this series of drawings does not plunge into despair. The impossible becomes the possible thanks to radical refusal. Mäkilä does not seek refuge; he seeks challenging and rendering encounters which also support and assist.

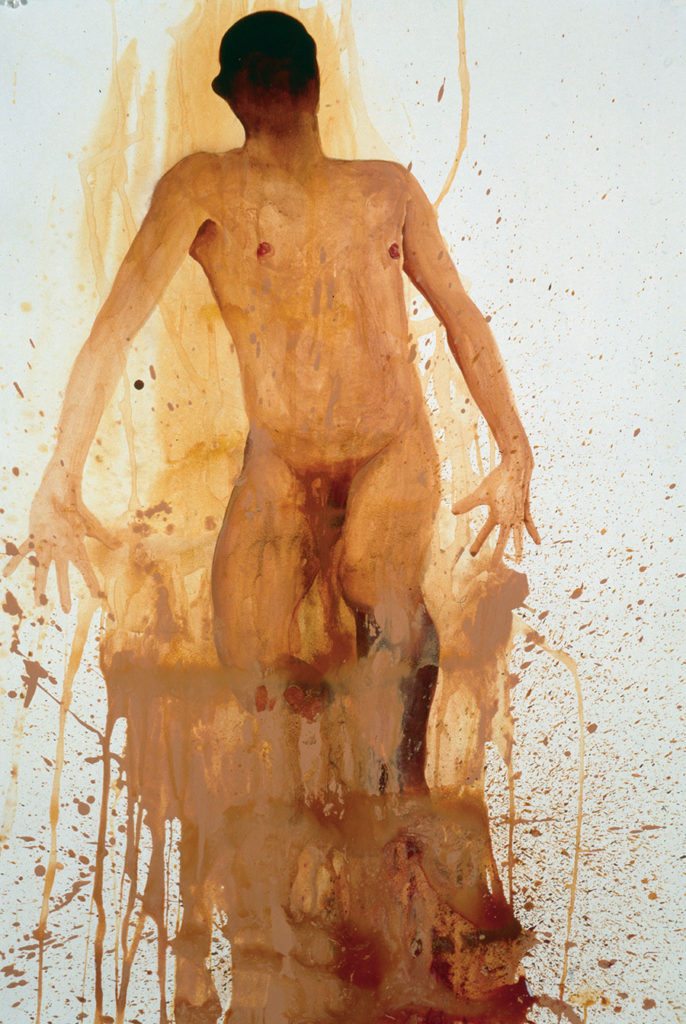

Mäkilä reveals, but doesn’t tell all. He challenges and provokes, tickles the cerebral cortex this way and that. In his series of large paintings the physical presence is breathtaking. Not exactly giddying, just simply strong: paintings on a collision course with Hell. They get to you, worm their way into your subconscious and make you to think. Father and son, hope and despair, the beginning and the end. And the rhythm: not cynical but fi ery. It bites and scratches, but occasionally also caresses. A gang of lads in the ruins of a deserted gym, brimming over with anarchistic strength, power and mischief. A boy who is simultaneously one and different, singular and plural. That awfully nauseating smirk and destructiveness that pulls and consumes. Or the man in the armchair in the snotty room surrounded by dogs. Dressed in a ladies’ summer frock, indecently exposed, a diaphanous scarf about his head, emphasising not concealing. Full of indication and supposition, degeneration and disintegration, yet not without its own personal pride and charm.

Mäkilä’s is a painterly physical presence that never leaves your mind at rest. A presence with a simultaneous relationship to the past, as well as a continuous dialogue with the present. A process that knows how to give and take, with thunderous applause and a quick slap on the cheek. It knows how to laugh and how to cry, at the same time and separately.

Mäkilä builds a whole from a resuscitated cliché. The totality of the exhibition is more than the sum of its parts. A claim that means absolutely nothing until we get the chance to experience, participate and see, and relate ourselves to how it happens. Actually and actively. Physically and spiritually present, relating, living and experiencing ourselves to the place, stumbling and staggering along the path. Beautifully, oh how beautifully. As a Gesamtkunstwerk the exhibition is a series of events in which Mäkilä can also provoke.

He never lets you off easily or allows you to have only unpleasant thoughts. The protagonist in his cartoon book Taxi into Van Gogh’s Ear is a mirror image of Mäkilä, but it’s a version of the man who carries another name. A fi gure that is just as mischievous as he is inimical. A fi gure by the name of P. Itikka [a midge but also a play on the word politics] who sometimes gets on well with the present, sometimes in hopelessly deadlocked meetings full of bluster and reserve, shame and ecstasy.

Mäkilä’s accustomed sharp, even dangerous mark subjects the viewer to the contradictory push and pull of supposition and observation. We ask because we have to. We ask what, where and how at the same time as we follow the story. A cartoon that functions equally well as a series of paintings on the wall or in book form. A cartoon strip that’s full of details that move in the border zone between the banality and fantasy of the everyday. Just like the short sharp sentence that concludes Mäkilä’s book, the pages of which are shown side by side in their original size: It looks like autumn’s coming.

An exhibition in which even the most inconspicuous work observes and follows us from the back of the room, nobly from on high, infi nitely tiny and yet so great in its smallness. Hands in front of the eyes, with passionate gaze, seeing it all and regretting what has been seen. It’s a wicked, wicked world, but still the promised land.

The small delicate fi gure of a boy in who so much and so little culminates. The before which is present in the now. The before which either opens or closes, makes possible or impossible that which we perceive and which shapes us through the now and the after. Those future pasts that cannot be bought, gifted, even stolen; that have to be faced and experienced.